YOUR JURY DOES NOT THINK LIKE YOU Social scientists studying how the human brain gathers and assimilates data have tried to quantify how the average human being gathers information. Their research quantifies the five human senses as follows: a. Sight 87% b. Hearing 7% c. Smell 3.5% d. Touch 1.5% e. Taste 1%

Donald E. Vinson, JURY PERSUASION: PSYCHOLOGICAL STRATEGIES AND TRIAL TECHNIQUES 184 (1993).

While that particular data is 26 years old, the reality that American society is now one of “visual learners” seems only more incontrovertible. From television to the Internet, Americans now learn through visual explanations.

“Talking heads” and the spoken word are relegated to PBS – people now expect pictures, diagrams, and animations in every aspect of their news. Unfortunately, most schools taught our brains to become verbal thinkers – thoughts themselves become internal conversations in words rather than concepts perceived the way any other profession invents ideas. Most trial advocacy teaching doubles down on the mistake, fueling the misconception that the power of our brilliant rhetoric can overcome the fact that most people think and, more importantly, learn visually.

We have been trained to live, think, and communicate in a single sensory state that does not connect to over 90% of the way people gather and process information.

This leads to multiple failures in the presentation of evidence to a jury – boredom, complication, abstraction. Any one of which renders your brilliant language choices irrelevant to the decision-making process of the people you need making a decision.

Our jobs then require us to change our point of view for the presentation of evidence. Arguments and examination need to be designed with an eye for how, and the means by which, a jury receives the information we want them to receive. This requires vivid thinking, reformed into a more visual sensory experience more often than not. And this does not mean just Power Point. Rather, think in the multiple different forms the courtroom allows visual communication in picture forms. A single picture not only unlocks 1,000 words – it actually unlocks a story, fully formed with all the connotations that can be taken from an image that represent a holistic concept. Fortunately, the law does not constrict a good trial lawyer’s imagination on persuading visually.

In the neuroscience of the way the mind processes information, the deepest process, after the initial sensory reception of information through the five senses and translating it through working (short term) memory, lies in long term memory. This is where life experience lies. Long term memory from experiences is where the concept of schemata lives.

Most schemas lie dormant in memory. The power of activated schemas is that they enter attention consciousness and are used instinctually, almost immediately, in problem solving. In this way, stored schemas (beliefs formed in long term memories) actually process information – the brain “subconsciously” accepts a data point or rejects it without consciously “thinking” about it.

Here, the “part” (the image) activates sense of the whole (the schema associated with the image). In this way, an image of John Wayne unlocks for that person any wealth of concepts, beliefs, and memories, and thus decision processing of the details becomes subject to the larger, deeper thought. For most, inside an image of John Wayne resides any wealth of beliefs about America, heroes, and their father. Thus, imagery provide connotations and thematic inferences well beyond the simple word. For example, a scale tilted to the side with eight persons standing against a single person on the opposite side will graphically convey the preponderance of the evidence better than “eight versus one.” A jug full of 7,300 aspirin can symbolize daily pain more effectively than a table with “Twenty-year life expectancy x 365 days = 7,300.” In a case about whether an owner has sufficient control over an independent contractor’s work, a simple picture of keys to locks signifies the concept that no one goes anywhere without the owner opening the door. In a case involving off label prescriptions, a rat in a lab with a syringe to its neck unlocks the implication that the company’s activity was an improper experiment without devolving into the law of off label use.

In a case involving electronic medical records being changed, a massive medical file storage suite of old style charts signifies the permanency of a medical charts. In a case involving trade secrets, a picture of a file marked “CONFIDENTIAL” in that 5 iconic red stamp may convey more than a blow up of the document with the business plan.

These visual anchors allow your jury to find the facts – to which you are leading them. The challenge is finding images that are concrete, universal, and convey the message you want. Visual images are dangerous in this regard. A picture can mean a lot of different things to different people (that is its power after all). Marketing studies show this goal can be achieved, but with work not normally in a lawyer’s skill set. The search for appropriate visual requires discussions with peoples like us who do this for a living. The simple power of an old school flip chart is that a jury experiences the visual creation (sketches and drawings are better but even words capturing testimony share this power) in real time.

These tools are not just imperative to give your jury what they want, these are the very simple forms of visually conveying information that they need.

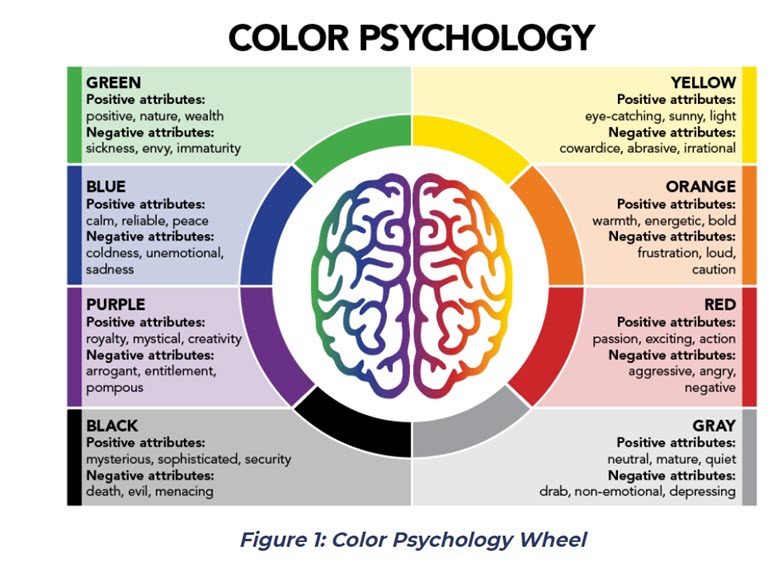

The Do’s of Persuasive Demonstrations a. Keep it simple • Use simple pictures or symbols to uniformly convey concepts; • Use as few words as necessary to present the essence of the thought; • Create and use recurring labels or titles for slides or blow ups to assist in giving context; • Try to keep each slide or visual aid to a single thought. b. Appeal to all the senses Jim M. Perdue, Jr., An Eye Toward Your Jury, 2020 Page 7 • Use effective color combinations for emphasis (e.g., black on yellow, white on blue); • Use color to convey meaning • Include auditory cues (let the jury hear a decedent’s voice, the sounds of a siren at the accident, the beeping of monitoring machines at a bedside);

Use aids that can be touched and manipulated (e.g., pass around an actual seatbelt latch, endotracheal tube, indwelling catheter, back brace, let jurors touch things). c. The means can be the key to the message • Use extra-large LCD monitors or extremely bright high lumen projectors with a good presentation screen to provide the maximum size for any images to be watched; • If monitors are used, assure yourself that there is no glare distracting the viewer; • Position demonstrations and projection screens for the jury/decision makers (not so you can be sure to read along); • Place blow-ups as close to the jury as necessary for legibility; • Place demonstrative aids in position to help your expert teach the jury; • Place demonstrations to cut off the jury from opposing experts

The Don’ts of Persuasive Demonstrations a. Overwhelm the visual exhibit with wordiness • Attempt to keep text to six words per line; • Assure the text is simple and understandable; • Keep the font size large enough to be legible (sacrifice words before you sacrifice size); b. Create “visual noise” • Keep graphic design relatively simple; • Avoid the use of excessive or extreme colors; • Don’t change font styles just because there are many choices; • Slide transitions, colors, fonts, and style should not be complex simply to show off the technology--it will distract from the message; • Be sure that any overlays or slide transitions do not clutter or obscure the underlying information; • It is often better to have multiple charts/graphs/time lines demonstrating a single parameter, rather than having multiple parameters graphed on the same chart/graph/time line. c. Use too much of a good thing • Trial is live theater, don’t let it become a movie. Movies are great, but live theater is a much more powerful experience for the audience; Jim M. Perdue, Jr., An Eye Toward Your Jury, 2020 Page 8 • Day in the life videos are most effective when used with a live witness, but the audience’s connection must still be with the witness on the stand; • Do not use PowerPoint for the entire summation of a case; rather, use the visual slides to emphasize key areas and evidence, but always remember to create personal moments; • Just because you have an exhibit does not mean you have to use it during trial. Sometimes less really is more.

By Jim M. Perdue, Jr. I.